Foreword

Dear English speaking reader, this is an automatic translation of the original French text.

If you wish to help to make a real text in English, your help is welcome. Do not hesitate to contact me at the address at .

Thank you, have good reading.

First Memories

Several people of my acquaintance having written a book recounting the memories of their childhood, I said to myself "why not me? Not to make a book but to give my children and grandchildren an idea of what I knew as a child. I regret enough not to know much about my parents' childhood.

I was born at Sampigny, in the Meuse, on November 7th, 1935. From my very early childhood in this village, I have no memory left.

I want to say right away that I only knew my paternal grandmother, who was then living in Sampigny, my grandfather having died, I still do not know when. On my mother's side, my grandparents lived in Schiltigheim near Strasbourg. I never saw my grandmother, as for my grandfather I saw him only twice, once during my first communion and once in 1959 during a trip to Alsace, but as he did not speak a word of French, I could never converse with him.

I wonder why, when we had regular contact with my father's sisters (aunts Léa, Fernande, Louise and Georgette), we never went to Alsace with my mother's brothers and sisters. She was the eldest of six children, she raised them in part, and at the age of 14, as her parents did not have much money, she was placed with an uncle, Louis Ducat who was a lawyer and justice of the peace in Bar-le-Duc. It was from that time that she started breaking bridges. Only his sister Marie-Louise who worked in Paris visited us regularly. Mom when she arrived in "France" did not speak French at all, until 1918 Alsace was German and speaking our language was strictly forbidden. She learned by reading a lot of books and especially those of Balzac. Everyone said she spoke well despite a slight Alsatian accent. It also served him well afterwards to speak German.

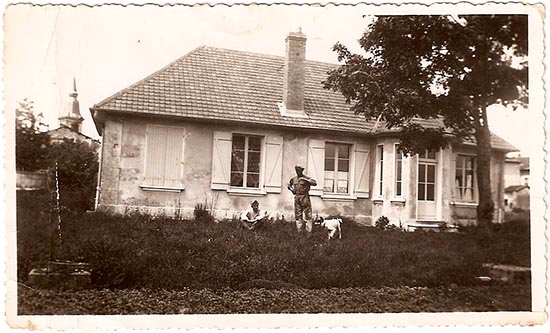

To come back to my first memories, they go back a little before the war: I was then in four years and we lived in Belleville, impasse marshal Petain, renamed general impasse de Gaulle for reasons well known. We stayed on the first floor, the owners Mr. Mac Farlan and Mrs. Bertrand lived below. I remember my cousin Yvette (Aunt Louise, her husband André Bourgeois and their daughter Yvette lived in Colombes) who was on vacation with us and who, on my way home, took off my shoes in the hallway of the house on the trunk surmounting the stairs of the basement. I must locate the location of this house: going up the impasse we arrived at the national road along the Meuse, this road is the national 64 which connects Belgium to Dijon. In peacetime it is the road of the holidays on the Côte d'Azur, but by the troubled times that we will know is the road of invasions and liberation, all the milestones of which I will speak were passed along this road.

One day, I did not find anything better than to follow soldiers who parade with music, mom looked for me everywhere and it is a lady who brought me back. Still in my memories, I come back to an image, that of soldiers in horizon blue who, exhausted, slept on the ground in the meadow street. It was also the birth of my little sister Christiane on November 13, 1938. It was the happy pre-war era when we could still buy toys, I remember a little white tricycle and a pedal car in iron. I also had some modeling clay and my dad was playing Hitler with his wick and mustache. I also remember an Easter egg with a pretty blue ribbon all in sugar. Subsequently I have never had a gift. One day when I played on a pile of bricks in front of our house, I fell, certainly on a sharp shard and I took off half of the ear, my father took me to Verdun on his bike, to a pharmacist who sewed it to me, I kept the scar a long time. I remember that my father's bike was orange, it was stolen from him and my mother's during the evacuation and they never had the means to pay for others.

The War, 1939-1940

The war was coming, it was in all conversations, my father was listening to the radio, and Hitler could hear his rhetoric on the airwaves. We went to the town hall to look for our gas masks. Close to home, lived two young comrades Julien and Genevieve Quenet, one day I saw their father in uniform, he went on the Maginot line, he was taken prisoner, we saw him again only five years later.

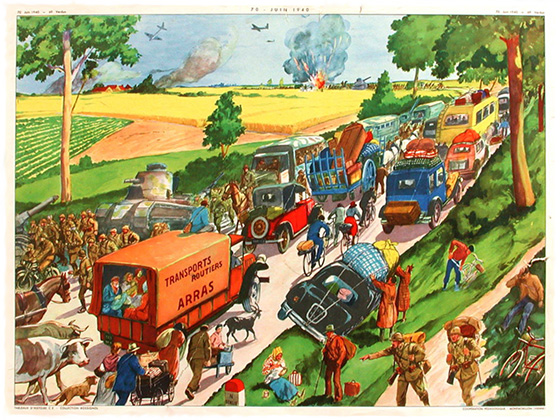

One afternoon while I was watching Mrs. Bertrand working in her garden, I heard a strange noise of plane, I said to him "madame it is necessary to return because one hears planes", she told me "you "she took me in her arms and we rushed into the basement of the house, she just closed the door she received in the figure at the same time we heard a huge noise. A bomb had fallen almost to where we were some time ago. It should not be a big bomb because I would not be here to tell it. Imagine the fear of mom who thought I had been killed. She shouted "Titi, Titi" that's how I was called, she was very relieved when Mrs. Bertrand shouted to her that we had nothing. Dad was sleeping because he was working at night, near the open window, he was awakened with a start, his bed covered with rubble. The only damage was the henhouse destroyed and the animals that were there. The whole afternoon was full of people to see the damage, it was a foretaste of what was coming. That day there was still a person killed, it was the baker Faubourg because this plane had dropped several bombs. Another time was crowded at the side of the road to watch a convoy of German prisoners, some had stones to throw them, we waited a long time and we saw nothing happen. On the other hand, soon after, we began to see columns of Belgian refugees, motley parades of cars, wagons, carriages, it was the beginning of a sad period.

The Exodus, June 1940

The events rushed: one evening, the rural guard came to tell us that we had to evacuate the next day, that trains were planned in Verdun station and it was the first great adventure of my life. I remember going up on the track and the steps of the cars were very high; What surprised me was that in Chalons it was lower, obviously we were at the dock, which I did not understand. Crossing the subway, a train passed over us, what a sound, I think about it every time I pass in this underground. In our compartment there were sisters of Carmel Verdun, they all seemed lost because some were cloistered for a long time.

We had to take several trains and in the evening we arrived at Nançois-Tronville, I think it was in Bar-le-Duc that a gentleman gave me a little race car red celluloid, I was fine but when we arrived at the house of the Josse - tenants of a house of Uncle Ducat where we were staying for some time - the lady told her that she was perhaps poisoned, that she had perhaps been given by a member of the fifth column (this was the name of an espionage organization that was never proven to exist, but there were so many crazy noises at the time) and in the morning I did not find my car. Mom confessed later that she had thrown it, that she had regretted her gesture. Another memory, a morning of the soldiers came to the house to tell us that we had to stay inside, because they were going to blow up the railroad grade separation that allowed the junction to Strasbourg or Neufchateau, he was a few hundred yards away. I remember the rain of debris falling all around the house. This grade separation has never been rebuilt. In Nançois also lived Aunt Fernande and her husband Uncle Henri Mangin, they were farmers and it is with them that we were going to flee on the roads of the exodus.

Here we went one morning, Uncle Henri, Aunt Fernande, Georges the son of the uncle, aunt Leah, her husband Lucien Burte and their son Pierre, a little older than me, who lived in Velaines. Uncle Henri had loaded a cart with all sorts of things, furniture, bedding, kitchen utensils and especially food that would be useful to us. Mom walked behind pushing the pram where my sister was, who was then eighteen months old. I remember the name of the horse, his name was Bayard, I walked beside him encouraging him "Hue Bayard, Hue Bayard". The uncle did not want us to climb on the wagon because, as he was very busy, he was afraid that the horse would die exhausted, we would have been embarrassed. When I was too tired, Mom also put me on the pram. We left by Nançois-le-Grand and on the national road we became part of the cohort of refugees. We crossed military convoys, which caused us to be strafed by German planes several times. Each time it was a panic, people would fling themselves to the ditches or run for shelter under trees. Uncle Henri remained standing near his horse, fearing that he would become frightened and run away. An image that made a strong impression on me, while a plane was shooting at us, a soldier on the platform of a pickup truck kneeling behind the cabin managed to touch him with his machine gun, it left leaving behind him a trail of smoke.

Our route: Nançois, Void, Vaucouleurs, Vannes-le-Châtel where we were caught by the Germans, roughly fifty kilometers for not much, in I do not know how many days because we did not go fast.

Passing Void, big mess, civil and mixed military. There were soldiers who were looting the cellar of a cafe, passing the bottles through the air vent. They said "another magnetic mine that the Germans will not have". Mom asked a lady in the village to boil a pot of milk, she refused - hello solidarity - luckily mom was nursing my sister, the bottle was always ready. The soldiers asked us to hurry up to cross the canal bridge because they were going to blow it up, which was done as soon as we passed.

The need for milk is felt for children, Aunt Fernande went to milk a cow in a meadow. The poor beast had not been treated for several days, she did not stop mooing, unfortunately her milk was no longer good and we were sick. We slept sometimes in barns, often under the stars, it was very beautiful. Once, soldiers stationed with a wheelchair gave us food: meat and beans. We slept in a cellar in Vannes-le-Châtel when the Germans burst, with their lamp they put in our faces, they all watched us, they brought out the men, they released them some time later , having made sure there were no soldiers.

On the way back, no significant facts except an abandoned colt who absolutely wanted to join us. Aunt Fernande had trouble chasing him because she did not want to be suspected of stealing her. There was all along the road full of destroyed equipment, and especially in the meadows, the dead cows, which spread a terrible odor. The night we arrived at Nançois, we found the farm occupied by Germans, they wanted to offer us coffee they had prepared in a bucket hygienic, this bucket had served the first husband of the aunt who had died of Tuberculosis, Mom told them but they said they had disinfected it well. In the early days, among the Josse, we had almost nothing to eat and we fed couscous left by colonial troops and trout caught with traps in the Ornain.

The stationmaster came to tell us that there were parcels in our name at the station, all the parcels were disemboweled and the things were scattered on the ground. There was even the dictionary that my brother Jacques still has. These cases had been sent by my father and despite all this mess they had arrived and nothing was missing.

I have not yet mentioned my father who was not with us. Indeed, when we left Verdun, he was mobilized as a railway worker and he had to stay on the spot. He could not accompany us on board because he was working in a switchyard near the Tavannes tunnel. When he was ordered to evacuate with the last train leaving Verdun, returning to the city by bike, he was arrested by soldiers who suspected him of espionage because theoretically there were no more civilians . He managed to exonerate himself and just take the last train. On the way this train was strafed and several people were killed in the cattle car where he was. This train went to Jussey (70) where he found himself in the middle of rearguard battles. My father was taken prisoner a few days, but since the Germans needed railwaymen, he was repatriated to Verdun.

Mom had no news and she was having a lot of trouble until the day the stationmaster came to tell Mom that my father was asking on the phone (obviously SNCF). Mom came back happy telling me that she had just spoken to Dad. I was convinced that it was verbal, because I did not know what a phone was, I felt a little frustrated. It was time to return, Mom had asked the stationmaster to report it as soon as there was a train to Verdun. There was one for Lérouville, but since he had not been instructed about civilians, he did not want us to borrow him. Mum paid a lot of money and asked the German officer who was there for permission to come up, he accepted, he even helped us to get on board: it was a freight train and it was 'was very high, it must not be forgotten that there was a high pram to climb.

In Lérouville, no train to Verdun, mom then decided to go to our grandmother in Sampigny. There is about eight kilometers between these two places, it was dark, there was a storm. Imagine a mother pushing a baby carriage with a baby in the rain and a little boy of the same five years walking next door. There was no light, all along the road were piles of ammunition, every flash mom was afraid that lightning fell on one of them. We arrived soaked at my grandmother's place who was not expecting us and had nothing to give us. I do not remember how we got back to Verdun. On the other hand what I remember is that all along this period, my sister did not stop to bawl and when it was reminded to him, it had the gift to make her angry.

Belleville, 1940-1941

During our absence our house had been visited, everything that had any value or utility had disappeared, there was practically nothing left but the furniture. He told himself that it was the case of the Belgian refugees, on the other hand there were things that did not belong to us, finally we recovered some of our belongings in the surrounding houses, our houses had to serve as "step lodging".

The most crucial problem that immediately arose was food, everything was disorganized. Mom was leaving early in Verdun to try to buy some food at the Felix Potin store, she left us alone at home, I had custody of my little sister. Very often she queued for hours, and when her turn came, there was nothing left and she returned empty-handed.

Two events from that era that I remember: one afternoon there was a storm, Mr. Mac Farlan, who was a hard philatelist, was sorting his stamps on his kitchen table. Suddenly a fireball came in, she made a turn in the room and she came out through the window of the toilet Our owner found himself propelled to the other end of the room, all the stamps were scattered, it s' is shot with a slight concussion.

In the winter the Meuse overflowed and the water flooded the cellar. When she retired, a beautiful pike remained a prisoner and enjoyed a meal.

Spring 1941, my parents decided to move, we visited several houses including one near the sports ground of Verdun, the park-of-London, pity that it was not retained because I could have attended free rugby matches. Finally the one that was chosen was the one located at 112 rue du Maréchal Pétain, also renamed to the liberation following the insistence of the owners who could not find the house. Ten years later, they did everything to kick us out to sell it, as it was the time of the housing crisis, my parents had a lot of worries. The house was large: three beautiful rooms and a kitchen on the ground floor, three large rooms on the first floor, a basement and a cellar, an attic. For me it was huge compared to what I had known. There was also a large garden surrounded by walls where there was a beautiful apple tree, a pear tree of large pears and a very small delicious. The fruits will be a blessing for the improvement of our ordinary and even those little pears Papa fired an excellent brandy. There was also a big henhouse where we could do breeding. A disadvantage all the same, the toilets were at the bottom of the garden.

The move happened in a rather folkloric way, my father had borrowed a wagon from the wood merchant, who had to come at night with his horse for the transfer. My father had asked comrades to help him, the cart was loaded and no horse. They hitched themselves up and fired the famous wagon to the bone. That summer it was very beautiful, one day I picked a bouquet of small white flowers in the garden, I had a fight, it was the strawberry flowers. My neighbor was a pretty little brunette girl, whom I immediately fell in love with: her name was Jacqueline and we spent long hours playing together, often with the merchant. Many years later, she married an American soldier and she went to live in the USA like many girls from here. I had very long hair with English hair, one day my mother cut them, what could I cry. I was going to be six years old and I had to go to school soon. I went home on my birthday, I remember it was a dark night, it was raining, not really ideal conditions to cheer me up. The teacher, Mrs. Jacquemot placed me near a boy whose at first I was bullied, he was kicking me under the table. If I complained, it was me who made me argue. I do not keep a good memory of the beginnings of my schooling. Fortunately it changed well afterwards.

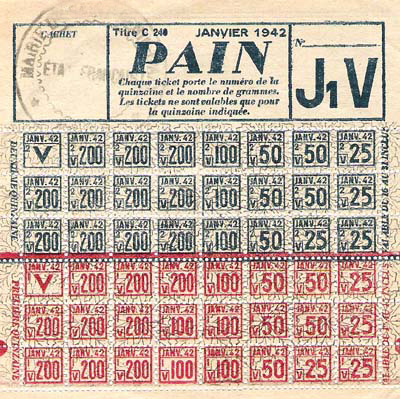

Restrictions

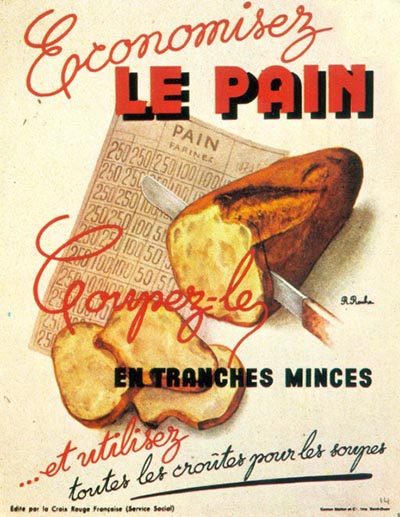

What marked the most all the years that followed, it is especially the lack of everything, in particular the food. When I see now how difficult people are and even cats, we were happy when there was something on our plate. It was the time of the tickets, to get anything it had to provide. Food cards were sorted into different categories: J1, J2, J3, and force workers, which varied the amounts allocated according to the age of the consumers. Once the noise ran that in the Marne it was not the same tickets that were used for the wine. the people rushed by the train to Islettes provided with bottles, a real parade but it did not last long.

I think what's been missing is bread. It's symbolic, the children were only allowed a ration of one hundred grams a day, it was quickly swallowed although it was of mediocre quality, it was really bread more than complete, some even said that the baker put sawdust in it to lengthen the sauce. The students in the school caught the scab, the itching started between the fingers of the hand, then it went up the arms, then we had the body all covered with crusts. We did not stop scratching, to treat us it was necessary to rub the body with a brush to pull us off these crusts and then give us a bath in a washing machine containing water where sulfur had been dissolved, then we plaster the body of ointment very fat charged with sulfur. It hurt a lot.

One day mom saw a German truck drop a ball of their famous "kaka" bread, she rushed to pick it up but she was not the only one to have seen it, another lady too, they have almost fought and it was a gentleman who passed by that lent them his knife to cut in half.

The meat was also lacking, 1942 was the hardest year, we could not even find potatoes, we had to settle for rutabagas, Jerusalem artichokes. Cooked in water, without gravy, it was not famous. We had started breeding well, Papa was growing two gardens, one behind the house and one in le Maroc near the station, but it was still too early to enjoy it.

In August 1942 I was sent to my grandmother's house in Sampigny. Mom was going to give birth to my little brother Jacques. For four o'clock, my grandmother was cooking the potatoes of her garden in field dress, she cut them in two, she put on the jam, they were my toast and finally I found it good. One thing we did not miss was the milk, we went to find it at the dairy, a brave woman who came every day from Vachereauville with her horse, about eight kilometers. She was called "Titine", in her shop she emptied her cans in a big tank and with a big ladle she filled our milk jugs over it. When we got to the bottom, the milk was so filthy that we sometimes had to filter it. We had to boil this milk and the skin that formed on it was precious, mother kept it and with this cream she made pastries, especially quiches with the eggs of our chickens, "chons" that we get by melting bacon to make lard and that skin. How good was this quiche! In the afternoon we could go for skimmed milk with which we made cottage cheese.

Papa, like many, would beat the countryside to try to bring back some food, eggs, a piece of bacon, some potatoes. He bought them, but in addition we had to give tobacco, coffee, the little chocolate we had. The farmers have made gold and the story of the laundry machines full of five thousand-franc notes is not a legend: at the end of the war, when the government decided to remove these tickets from the circulation in By replacing some of them by family, my parents, who did not have any, were much solicited to exchange for them, a little vengeance they refused. You should not be caught by the gendarmes because they confiscated what you had, it was not lost for everyone. Papa says that on the descent of a train in Verdun station, the gendarmes opened a boy's suitcase, there were some provisions in it, the gendarmes took it from him. A German feldgendarme who had seen the scene, "shouted" them as rotten fish, made them empty their bags which were full of victuals certainly confiscated, he told the boy to fill his bag and gave the rest to the other travelers.

For clothes, it was the same story, you had to register at the town hall and from time to time our name was posted for textile vouchers, for coal it was the same thing.

Winter 42 was very cold, we lacked wood and coal. To put his snack on, my father had a leather bag and he sometimes brought home a big engine briquette that he had had by begging a mechanic, or coke he stuck in the pile of the station. referrals. It was bad fuel and it was not hot at home, especially since we only had one cook. To go to bed, we took our brick wrapped in a towel, it brought a little heat in the bed. Dad also made a cut of wood, but it would be necessary to wait the following year to return it. I see Mom doing her laundry in the tub outside, in the icy water, she went up from time to time to warm up. We even had to bring our log to school because there was no heating. Life was really hard.

It was the era of the D system, everything that could be used was recycled: all the old knits were unraveled, the washed wool and a new sweater could be born in many different colors, the excess blankets were transformed into a coat or panties because there were not enough fabrics to make trousers. I can still see my mother poking for hours and even at night to make clothes on her pedal sewing machine. The girls' coats were lengthened and the shoes were stripped to excess, with all sorts of leather or rubber falls, until death followed. So we wore wooden shoes and even clogs. I went to school in clogs, dressed like everyone else in the black cloak, short breeches, black blouse, Basque beret. There was no jealousy, everyone was dressed the same way. The hooves did not go badly to slide on the frozen ponds. To replace the silk stockings, the women had found the solution, they tinted their legs with chicory and then with a grease pencil they were sewing behind.

At that time everything was valuable, the least piece of wood, the smallest piece of scrap metal, besides it was imposed on non-ferrous metals for the German industry. Paper, cardboard, everything was recycled or resold, the bottles were recorded, the box springs, the mattresses were rehabilitated when the need arose. There was no problem of landfills because they were rather emptied than filled. The bicycle tires were replaced by garden hose or rags. Overnight, households had a roaster to grill barley instead of coffee. In all the gardens there was planted tobacco: I remember my father drying the tobacco leaves on the stove after soaking them in salt water, it was a horrible tobacco that may not be for nothing in the cancer that won it years later. The rabbit-skin merchant went into the street singing "Skins of rabbits, skins, skins, skins of rabbits skins" and we sold him the skins of rabbits that we had killed, that made us a small room.

1943-1944

hanks to the garden and the rearing we started to undergo a little less restrictions, but everyone had to give a helping hand, among other things to get grass or dandelions for rabbits, snails for hens. The days of canning mobilized everyone: it was necessary to shell the peas all morning, then in the afternoon to put them in bottles with small carrots, it took hours to fill these famous bottles. For the quetsches it was worse, it was necessary to cut in four and put them by the neck, work of patience. After we had them sterilized in a washing machine. There was no interest in missing the sterilization, because then the bottles exploded or when we removed the muzzle, the cap was jumping all alone and all the kitchen was recreated, not to mention the smell. Another day we went to pick some peas on an old airfield which was under the lime kilns of Haudainville and which had been plowed. What we picked was weighed, and half was for us. That day it was very hot and we were dying of thirst.

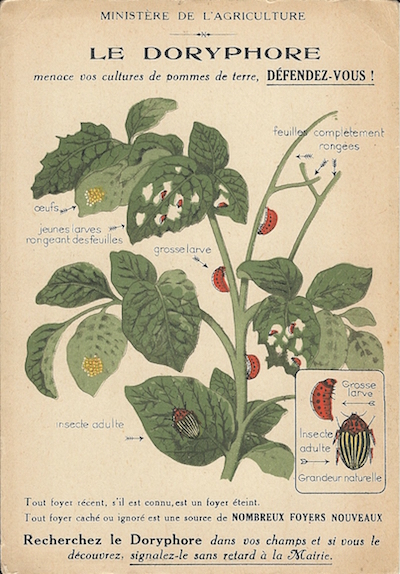

With the school we also went to collect potato beetles in the potato fields. These creatures swarmed, it was a calamity, and this is also the nickname given to the Germans, because they said they had arrived with them, which is wrong because it is the Americans who have made us a gift at the war of 14.

To compensate for our lack of food, we were given a spoon of cod liver oil before each meal. If there is something hard to swallow, that's it. At school we were given a biscuit caseéné every day, a kind of snack. One day the stock was stolen by students, so we were deprived of it for a month. One thing is certain, it is that among city-dwellers, there were no problems of obesity or cholesterol. On the other hand, many people had tuberculosis.

To stay at the level of food, it must be in 43, we had the visit of the Bourgeois family of Colombes. Mom had made a potato cake, Uncle Andrew could not believe it, he said several times "Augustine are you sure we can eat it?" ". I went sometimes to my aunt Fernande's house in Nancois, I arrived at the train around noon, the first thing she did to me when I saw her arrive, were fried eggs with a big piece of butter, since I've been enjoying of this dish, then after it was the bacon soup. In the country women and men went to the fields, before leaving they prepared this soup which they let cook all morning in a cauldron suspended in the hearth of a cook Maillard. This stove had the particularity of having a hearth below with a rack where was suspended the cauldron, and also a fireplace and a baking oven. At noon the soup was cooked just in time, it was the two meals of the day, noon the soup, the vegetables in the evening with beautiful fat fat bacon that trembled on the plate. It was the menu of every day, on Sunday a rabbit or a chicken was sacrificed. It may be simple but for me it was real treats …

These restrictions did not stop with the war. At liberation we had a few months of euphoria including white bread at will but, since 1946, it was necessary to start tightening the belt. It was at this time that we ate corn bread, it had a beautiful yellow color but it was not famous. It was in 1947 that my parents decided to raise a pig, but it eats these little animals and to feed my father had to give a hand to a farmer in the village of Bras, Mr. Blanchet, in exchange for apples of land or grain. I too went to work during my vacation, alas, for not much, because the farm burned and these poor people suddenly found nothing. The following year I went to work at Vachereauville at Monsieur Olivier's. The advantage of this work was that we were well fed.

On the farm we were mostly employed for the harvest, which then required a lot of labor. During the day the farmer was cutting the grain using the combine harvester which was pulled by a horse, this agricultural machine had been brought by the Americans to the war of 14. This was already a huge progress, before he had to mow and make the sheaves in their hands, now they fall off the machine. In the evening it was necessary to put the sheaves in pile so that they do not take the humidity and to reopen the piles the following day. After a few days, when they were dry, they were loaded onto a cart. It was quite an art to do the trolley because it was not necessary that it collapses during the trip. When we arrived at the farm, we had to unload them and stack the sheaves until the threshing that was done some time later, and there too it took a lot of people. A contractor brought the thresher which was a huge machine. In principle, the women placed themselves at the top and the men passed the sheaves from which they cut the strings and spread the ears on the carpet, others took back the sacks of full grains and still others put the straw in pile. At noon everyone gathered around a good meal. Today with the combine harvester all this is done at the same time by two or three people.

To go to these farms, I had a bike made of an old woman's bike frame with wheels of 700, without derailleur, without lighting, with a handlebar "daddy" that I had returned to make it look like to a racing handlebars. I had fun doing the zouave with, so that I had managed to break the saddle and I had replaced by a sneaker, which earned me a lot of jeers. It did not prevent me from going out in the morning and returning at night.

Our pig was particularly pampered, my father cleaned his cabin every day, he also changed his straw and as soon as Adolf (it was his name, because Hitler) had finished eating, he filled his trough with water. It was there that I realized that a pig liked to be clean, he took a bath and rolled in the straw with enjoyment. We liked to play with him and when at the end of the summer the garden had been harvested, we let him go and he shared our games, my brother even climbed on his back. We were a bit sad when we had to kill him but it was for a good cause. In Lorraine, there was a tradition, when someone killed the pig, as there was no fridge or freezer, he distributed the coal to his neighbors and friends: a piece of pudding, a bowl of cheese head , a grill, anything that was not going to the salt or was not transformed into the famous sausages that were drying in the stairway. We managed to spread these kills and when we heard a pig roar in the neighborhood, we knew that we would have something good to eat.

For my first communion in 1947, we invited grandfather, grandmother, uncles, aunts, cousins, in all about twenty people. It was the first family reunion since the war, it was joy but it had to be assured. Mom milled kilograms of wheat in her small walled coffee grinder, sifted the flour in one of her stockings, which allowed her to make cakes. Almost all our breeding went there, because our guests stayed several days with us. My parents had made savings during the war because there was nothing to buy, everything was invested and the following times were hard.

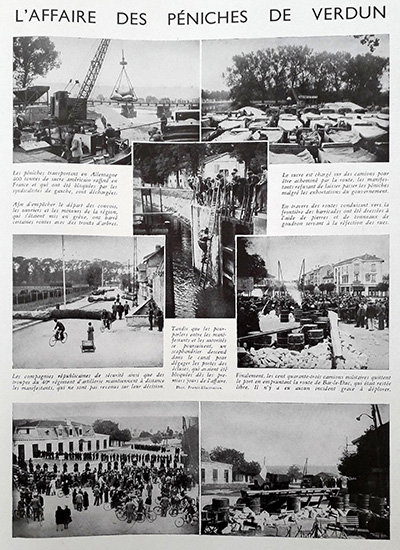

That year, there was also the famous story of sugar barges, two barges stopped at Verdun, people knew that they were loaded with sugar to Germany, while we lacked . We used molasses obtained by cooking sugar beets. There was a real riot to prevent them from leaving, even the Lorraine miners had come with their helmets and their picks. It was necessary to involve the army and the GMR (ancestors of the CRS) and with tear gas the protesters were dislodged, the sugar was loaded on trucks and he left.

|

|

(Real size page)

Daily life

Our life as children was obviously marked by the seasons, by the school but also by the church. At that time the majority of people were practicing Catholics. The days of rest were Sunday and Thursday. On Sundays we had to go to high mass at 10 o'clock, then to vespers at 2 pm and to salute at 6 pm on Thursdays we had to attend the 8 o'clock mass followed by catechism. There were still the novenas where you had to go to the evening prayer, every first Friday of the month obligatory communion at the 7 o'clock mass, the holy week was the way of the cross at night.

The boys had to be altar boys. For a week, for two, every morning we had to serve Mass; a quarter of an hour before, at 6.45, the bell had to be sounded. In the summer it was about the same, but in the winter, coming out of a house not too hot to go in the cold and the black (the public lighting was non-existent), to enter a church where everything was also black, this was not the joy. I do not know if today many parents would accept that. There were also feasts with a procession, the faithful parade in the street singing hymns, the banners were out, the priest (the abbot Naviaux, a good man we loved but who grew out of holy anger) was him Under a canopy worn by four men, he wore the monstrance. In each street, the people of the neighborhood made a repository where the procession stopped to say prayers. There were also the rogations: in the spring, for several days in a row, people paraded in procession around the village, in the cool morning dew, reciting the litanies of the saints to promote the cultures.

We had permission to leave the school to serve a wedding or a funeral, it had a good side because it brought us a small room, sometimes a big one when the married family thought about it. We had noticed that the more simple a wedding was, especially on Saturday nights, the bigger the room. At baptisms we had a cornet of dragees with a ticket slipped into it. One thing that is not done anymore, at the exit of the church the parents of the baby throwing pills at the children.

>On Sundays and Thursday afternoons we went to patronage, we were supervised by young seminarians from the major seminary of Verdun. There, that good memories: as soon as they arrived, they fell the cassock and put in shorts and we went on the football field to make all sorts of games. Some Thursdays we were leaving in the woods to make a treasure hunt, we never lost anyone. In the winter they passed silent movies like Charlot or Buster Keaton and especially comics in fixed films, that's how I saw my first Tintin et Milou: Le Secret de la Licorne and le Trésor de Rakham le Rouge as well as Jo, Zette et Jocko. It was a time when we did not know TV and we rarely went to the movies. In the hall of the patronage the boys were installed on one side and the girls on the other, it was not necessary that they look on our side because the nuns who framed them prevented them as if it was a sin. Besides, the girls envied us a lot because if we had a good time with the abbots, they were bored with the nuns.

We also did theater and I remember that at one of those sessions, there was a lottery, the jackpot was half a pound of butter and it was mom who won it. Very happy, when she came home she wanted to show it to my sleeping father, but she dropped it on his nose, I do not know but I felt that Dad did not really like butter.

The school

There is certainly not much difference between the school I knew and today, except that the school of that time was a very respected place, it was the school of the republic where we learned to become a man. The school was split into two on one side the boys 'school and the other on the girls' side, a wall and a high wooden door separated the two, but there were holes in the door and sticking to it. our eyes we could see the girls.

The teachers were, with the pastor and the mayor, the most important people in the village. Many times our parents could not receive a good education, they had to leave school early to help their families, family allowances did not exist and families were often numerous. My father, being a breadwinner, had entered the Goldenberg factory in Vadonville: at the age of twelve, he had to maintain the fire for the steam engine and if the pressure went down, he would kick his buttocks. There were also a lot of immigrant workers, especially Italians who had been brought in after the war of 14 to rebuild our country, they did not speak or very bad French.

The ambition of our parents was that their children know how to read and count and that they pass their certificate of study, the passport for life. If we had a bad score or if we had a punishment, it was almost always doubled. When the master angered (which happened quite often) and broke a rule on his back or hit us with his fingertips, we had no interest in complaining. I see the master with his gray blouse covered with chalk, we wrote pen with purple ink, we often had on the fingers, it remained the symbol of our schooling. The private school, let's not talk about it, it was reserved for a bourgeois elite and we were virtually unknown.

The most anticipated moment was Saturday afternoon, which was reserved for practical work. We have learned many things, many of which still serve me today. We learned to make wooden objects, make plaster casts, small electrical fixtures, model aircraft. For Mardi Gras we made paper mache masks, we also learned how to make drizzle with ink, a fine grid and a toothbrush to carry out the programs of the end of the year party. We had workshops of three or four and the master passed among us to help us. When our gliders were finished, we were going to fly them in the coast, over a quarry, some went so far that we could not get them back. On a map of the geography of mute France we had established electrical circuits and when we were questioned, instead of reciting stupidly, with the help of two touch points we had to find the departments, prefectures and sub-prefectures. Every time the light went on and the ringing sounded, we had more points.

The month of May was the month of the chafer, it was full, it was enough to shake a tree to fill a bucket, we dropped some in the class, which angered the master and we spent long minutes trying to catch them.

One thing I did not talk about yet was the alerts: every time the siren sounded, we had to go to the basement of the town hall and stay there until the end siren. We were lit by a poor kerosene lamp, no way to work, so we sang, the master told us stories or asked us riddles (I think it was to avoid being afraid). Over the years, there have been more and more and we spent more and more time in shelters. We did not realize the danger and sometimes when we did not know our lesson, not to be interviewed, we hoped that there would be one ... To be honest, it never happened during these alerts.

The certificate of study was very important, it was fourteen years old and with him the majority of students entered the working life. For many it was the end of their childhood, it was the object of a party. The teacher had a motorcycle, he hung a trailer behind, he had two or three laureates go up there and made a tour in the village, the young people shouted "we got it, we got it", it was the travel certificate of studies. This teacher was called Mr. Perignon, often I was afraid of his anger but he left me good memories.

Holidays

The winters of war were very cold, the Meuse overflowed and flooded the plain, which made us beautiful skating rinks. Summers on the other hand were very beautiful. There was in Belleville, on the banks of the Meuse, a locality Le bateau-coulé: this boat was an iron barge of the Ponts et Chaussées which had sunk during a flood and the Meuse had brought all around the sand, this which was a beautiful beach. This is where we learned to swim with rush boots. The whole village met there in the afternoons, the mothers came to watch their children, took the opportunity to knit and chat with each other. On Sunday fathers took their bundle of fishing rods and tried to improve the ordinary with some fish.

Dad was never with us because as he worked in three eight, it was either morning, evening or night, for eight days. He was resting a week on Monday, the week after Tuesday etc., he had a Sunday every two months so his life was completely out of step with ours. In addition, all his spare time was used in gardening or, in winter, making wooden cuts in the red zone (battle places of the 14-18 war). This war not being very far, the vestiges swarmed, all that can leave behind them several months of war: trenches that we had to cross, barbed wire in which we took the feet, helmets, various weapons and especially shells by thousands . When he started a cut, the woodcutter had to clear the ground, he was trying to fill the trenches with brushwood, the shells were picked up and piled up at the edge of a path in order to be removed by the demining company. As he had to make a fire to burn what was not useful, He was doing a pile, lighting the fire. As soon as he had taken, the woodcutter was saved and sometimes when he came back, instead of the fire there was a big hole because under a shell had exploded. There were some accidents. The trees were riddled with shrapnel and when sawing, there was often a characteristic noise that indicated that the saw had fallen on something that did not please him, so it was necessary to play the file to sharpen the blade. Today nature has regained its rights and when I return to these places, I do not recognize the landscape of that time.

To return to fishing, Dad was not patient and could only stay a few minutes in place. A fishing trip for him turned into a hike because he was traveling for miles, and the two or three times he wanted to go fishing, he always came back empty-handed to the chagrin of my mother. He still managed to bring us a little roach who wanted to commit suicide. When we came back from swimming, we brought back some willow branches to feed the rabbits, because it was so dry that there was no more grass.

I jump from the cock to the donkey but one day mom took me to the hospital in Verdun to have tonsils operated on me. Already, we walked about three kilometers, then it's almost a scene of nightmare: in the operating room I was surrounded by a kind of oilcloth strap with belts, a nurse m I was standing between her legs, I was put in the mouth a kind of clamp to keep my jaws well open and then the nurse stuck a tampon of ether under my nose to sleep. When I woke up, the surgeon was not finished and he was still pulling me out of the big cotton swabs full of blood. It took me a long time to feel the ether. To return in the evening we still used a taxi, I think this is the first time I ride in a car.

The facts of War

In the early years, there were no significant events, we saw the German military almost everywhere but it was quiet. I immediately want to say that the Germans have always been correct with us except the time when there was sabotage at the railway depot. The resistance had just blown up the pump, which was used to supply the locomotives with water. That day they were aggressive and all passersby were searched under the threat of machine guns. As it was not far from home (we lived about a hundred meters from the railway line), we did not go far.

I do not know when but a family came to live near us, we never saw them, just once a girl was out at the door, I still see her face. One morning I heard that they were Jews and that the Germans came to pick them up during the night. We never saw them again.

Things changed in the course of the year 1943: first alerts more and more numerous especially at night, mom woke us with a start and we had to go down to the cellar. We started to hear waves of planes in one direction and a few hours later in the other. Mom was very scared, she was often alone because dad was working. By day there were air battles, the fighter planes left trails of condensation in the blue sky and people were trying to interpret them. Some people saw numbers and said that they were announcing a bombing for such a date. From time to time they dropped their extra tanks, at first we thought they were bombs because they had the shape. As they did not explode, brave people went to see and their use was quickly found, they were transformed into a fishing boat by putting them two by two with a kind of bridge on it, somehow the ancestor of catamarans.

One night in August 1943, it was a beautiful weather, without a cloud, during an alert we heard hundreds of planes, we went out, it was a beautiful moonlight. In the sky it did not stop to pass in impeccable formations, in groups of four, they were going to bomb Germany. For us it was the hope of deliverance. A few hours later they were ironed but in small groups, some making a funny noise, certainly that they had been touched.

Another night mom woke us up frantically, telling us to hurry up to get dressed. Through the shutters we saw glimmers. It had just been an air combat and an allied plane, certainly hit, had dropped its load of incendiary bombs on our neighborhood (it was pure chance because as all the lights were off he could not know where he was leaving them) the houses between us and the railway were burning. When we went out to save ourselves, bombs on the road threw real geysers of flames like big Bengal fires, and we had to slalom between them to advance. These bombs were made of sheet metal, hexagonal in shape, about six centimeters in diameter and thirty in height. There was a steel weight in the ass, so that they fall vertically. Many of these weights have completed their clipboard career. As just dad was not there, he was on duty. Like everyone else we ran away, mom pushing my brother's pram, my sister and I next to go we did not know where. People we knew a little bit, Mr. and Mrs. Wintrebert who lived a little further away stopped us saying that there was no more danger, and they invited us to stay with them. We stayed there the rest of the night, then every time there was an alert, they would pick us up. We have remained very good friends. My father, who saw the neighborhood burn, made a lot of bad blood for us and the house, he was not allowed to leave his post.

Obviously the media were in the pay of the occupier, to have real information it was necessary to listen secretly Radio London, while it was formally forbidden. Many people were caught because they had not taken the precaution of changing stations after listening and perhaps some were shot as hostages for their negligence. When he could, my father listened to him, but he had told me never to talk about it. I remember "Here London, the French speak to the French", the song of Pierre Dac "Radio Paris ment, Radio Paris ment, Radio Paris is German", all with attempted jamming by the enemy who in reality do not did not scramble much. What intrigued us was the personal messages that made no sense for us "The postman has a wooden leg, I repeat the postman with a wooden leg" or "Marcel has a red sweater, twice But for the resistance to whom they were destined they were orders or information. Remember the "long sobs of the violins of autumn" which warned of the landing. We began to hope when we experienced the setbacks of the German army in Russia and then in Africa. I was very young, but I was passionate about all adult conversations, so be careful about what you say in front of children. It is also by this radio that we learned the landing in Normandy. There was a German railwayman in the switch-room where Dad worked, a bahnhof as they were called, who was there to watch. This man was trying to bond with the French, but they were wary when he asked them what the English had said. One day he brought a radio and as there was no power socket, he showed how to do it: break a light bulb and plug the plug of the post on the two metal wires of the socket, like that Frantz was his name, could also listen without risk of being caught. He was anti-Nazi, the French railroaders had offered to hide it at the liberation and then give it to the Americans. He agreed, but eventually he left with the army routed. We have also heard some machines passing above us with a funny motorcycle noise, it was, we knew then, V1, these flying bombs intended to fall on London.

June-July 1944

There was sabotage everywhere, the trains were derailing one after the other to delay the reinforcing troops on the Norman front. One day my father was in the morning, he had to return at one o'clock. We did not see him coming, as usual mom was worried. He returned at the end of the afternoon, white as a dead man, sick, he told us what had happened: a military train had derailed in Verdun station, in a particularly chosen place, he was barring all tract. Furious, the Germans took him down the station and had a firing squad aligned, the stationmaster who was scared was doing everything to drive him, while the chief of the depot defended him, explaining that it was impossible for him to derail a train. He knew what he was talking about, he was the leader of the iron resistance network. Finally, after much talk and the promise to restore traffic as soon as possible, Dad was released and allowed to return. He told us that what hurt him the most was that he could not say goodbye to us.

The German troops also occupied our school in June, and we had to go to the Faubourg school three kilometers away. The children of the Faubourg went there in the morning and in the afternoon. One day the wooden sole of my galoche split in half lengthwise and at each step it pinched the sole of my foot, I had to walk barefoot and I arrived at home this foot bleeding.

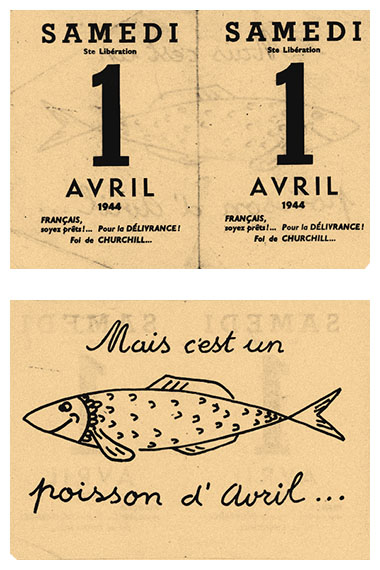

On April 1, 1944, militiamen were driven by throwing leaflets, one could read "The Americans have landed" but by unfolding them there was a beautiful fish and it was marked "April Fool".

The Liberation

In August 1944, bombing of railway facilities was becoming more frequent. As we lived near the railway line, and especially as there were two bridges, one on the Meuse and one on the road, we had to go to the house of Monsieur and Madame Masson, who lived in the coast and of which part of their house had been requisitioned. They had four children, two girls Genevieve and Odile, two boys Rene and Louis who was about my age. At night we all slept in the cellar, next to each other on a line of planks. It was already very hot and to top it off we were forced to have blankets for fear of being cold.

We started to see the German troops retreat, they were heading in the direction of Sedan, at first in a semblance of good order, it amused us to see them and, a kid idea, we pretended, Louis and I To put them into play with pieces of wood did not please one of them and he did the same with his machine gun. I think if my father had not caught us, he would have shot us. Then, it was a real outburst, worse than we had known in June 40: all that could roll was without stop, trucks, cars, cars on horseback and even carriages and wheelbarrows. The guys looked completely haggard and exhausted, when they heard a plane, they panicked and flung themselves on their stomachs. It was a real revenge to see them that way. On August 30th, the cannonade was heard getting closer. In front of the house where we were, lived a couple of militiamen, they paraded with their beautiful black uniform at the time of the splendor of the Nazism and we were afraid of them. A big black car came to get them, the woman ran down, tearing her stockings, to the delight of the spectators. We never saw them again, fortunately they left, because they would have spent a bad quarter of an hour.

The noise of the fighting was heard louder and louder. In the night we heard jump the bridges over the Meuse, then strangely the passage of troops was interrupted. Mr. Masson and my father went up on the roof to see what was happening. In the distance they saw as houses advancing in pulling, the American tanks were covered with a red fluorescent tarpaulin that shone under the moon to be recognized by their aviation. There was still a funny episode: there was also a couple of seniors who had been lodged with us and whose gentleman, a retired teacher, was losing a little head. He was struggling to get down to the basement, while the noise of the battle was raging he kept saying "but what is this pandemonium" But what is it that this pandemonium? ". In spite of our anguish he managed to make us laugh.

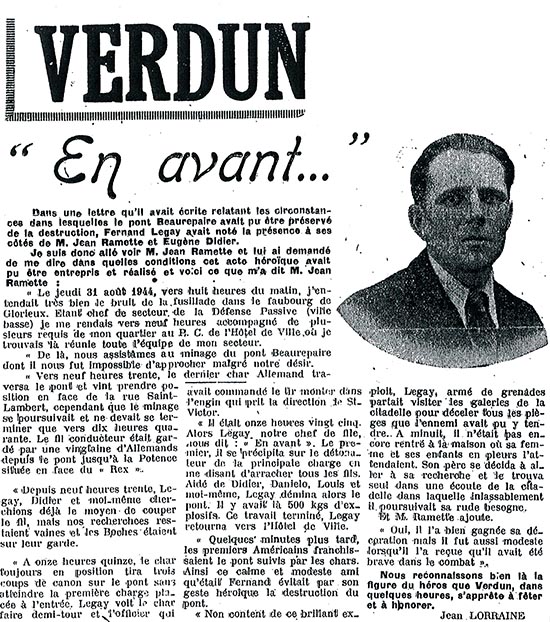

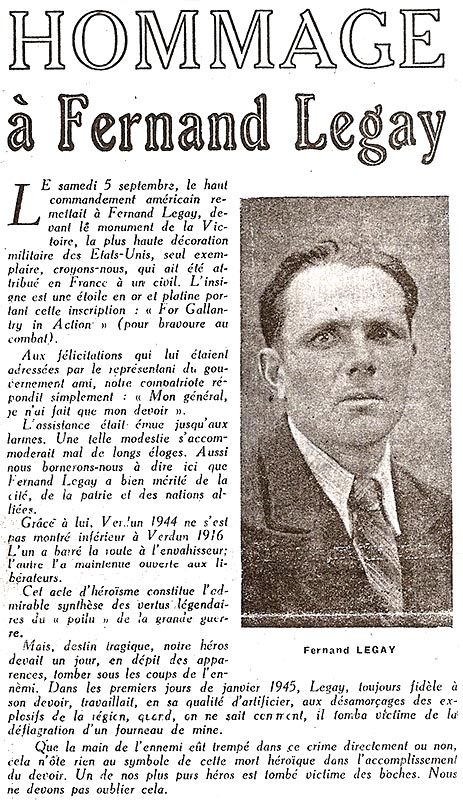

All the bridges had jumped except one, the Beaurepaire bridge: a Verdunois, Fernand Legay, who was artificer and resistant, despite the presence of the Germans, managed to cancel the firing of the mines. Seeing that the bridge did not jump and that the Americans were going to rush on, the enemy who had considered resisting on the Meuse fled (the newspaper articles report better than me these exceptional events). By his courage, this man has spared a lot of damage on Verdun and many human lives, for all Verdunois he was a true hero. Unfortunately, he died some time later, on January 9, 1945, while continuing his dangerous minesweeping activities at Fort Landrecourt. It was said that he jumped on a mine. Yet, a few days after the liberation, we heard on the radio waves Strasbourg still German "You le Verdunois Legay everywhere you go we will make you the skin, the bridge did not jump but you will jump" which leaves many doubts about his "accident". His son, Mr. Guy Legay, to whom I owe the documents, confirmed these facts to me. His name was given to the bridge he had saved. He left five children and to help this family so hard hit, school children sold postcards. My grandmother had told us it was a cousin, we were not sure, but after genealogical research I now have the proof.

Another very brave man also scored this day. We waited for the arrival of the Americans and we saw from the top of the coast armored vehicles. The people present shouted "Here they are". Suddenly, these vehicles began to fire at the machine-gun on the windows where a tricolor flag was floating. We then realized that they were Germans. Quickly we rushed into the cellar and Madame Masson had the presence of mind to camouflage the entrance to the cellar with fagots that were there. The armored cars stopped right in front of the house and by the air-vent we heard screaming orders in German. We were afraid that they would throw a grenade at us by the air-vent, we would all have gone there, they did it at the bakery opposite. I performed a heroic act, the cat of the house had made little ones and I took them in my arms to protect them.

There was an exchange of fire. Just as we had seen armed young men and women wearing the FFI armband down the canal, we thought it was they who were intervening. Suddenly the Germans turned around. After some time we heard a passive defense lady calling and asking if there were no wounded, what a relief! What had happened, a man, Mr. Maury, hiding behind a pile of sand a hundred meters away, alone with a rifle of the war of 14 and with eight cartridges managed to kill the German commander. Seeing that there was resistance they did not ask for their rest and returned from where they came from. Fortunately because a little further on the square, the population was gathered to sing La Marseillaise, burn enemy flags and mow the women who had a little too sympathetic with the occupant. If they had gone so far, they could have made a nice card. To paraphrase Churchill, many people owed their lives that day to very few people.

We only saw the Americans the next day. How beautiful were our liberators on their beautiful vehicles marked with the white star, and generous with that: they threw us all kinds of food from their rations, things we did not even know, bags of nescafe that have made the happiness of our mothers weaned for so long, cases of three cigarettes for fathers, matchbooks, chewing gum tablets and especially cans of a little bit of everything, chocolate bars, fruit pastes, sweets, everything we have been deprived of. Santa, for me, is an American soldier on his tank.

The next night we were bombed, one-ton bombs fell, one close to the shelter in the square I mentioned earlier. The people who were inside felt the earth tremble. Fortunately they did not explode, except one near the Saint-Maur orphanage in Verdun and one down the rue Saint-Pierre. German munitions were of increasingly poor quality, often made by deportees and workers raised in all sorts of countries, they did not put a lot of heart into the work. In any case it was another miracle. One of these bombs is on display at Verdun City Hall.

We were allowed to go home. The lack of everything was still felt. People went to loot the barracks abandoned by the enemy, many men more or less found themselves dressed with what had been left, clothes of a quality more than mediocre which they could not make a long use. I remember, among other things, pieces of black soap that did not want to melt. In the station of Verdun had remained a wagon loaded with boxes containing parachutes in artificial silk of a salmon red, overnight we saw walking women and children dressed in shirts or blouses of a beautiful tango color. The Americans were rebuilding the railway bridge over the Meuse and as they were fond of fresh fruit, we went every evening to offer them apples or tomatoes in exchange for rations. They were also very fond of my father's brandy. They had opened a dump at Bois Lecourtier and as they were throwing fat, we were going to get everything we could. They threw boxes of rotten oranges, we looked for the least damaged and they were the first oranges that I ate.

There was a prison camp at Verdun, their kitchen had been set up in the employers' room of Belleville. The children of the village queued in their wake to beg for some remains. I suspect Americans are making more food than necessary to give it to us. As it was often very spicy, Mom lengthened the sauce with some potatoes and we had for the day. These were kind of the restaurants of the heart before the hour. We were not proud at the time, I am well placed to understand the people who use it.

To make a little money, mom began to wash the linen of American soldiers and she was well seen because it made them impeccable, well ironed. It lasted a few months and then the life gradually resumed a semblance of normal course.

This is also the time when we did what we could call bullshit. As he was dragging ammunition everywhere, our favorite game was to blow up everything we found, bullets of all calibres, grenades and even DCA shells, especially in the fort of Belleville but also in the shelter on the place. The country guard tried in vain to stop us but we ran faster than him. A chance that there never was an accident. I was only about ten years old, but we were trained by "grown-ups", one or two years older than us.

December 1944

The war seemed to be moving away. It was easy to see military convoys, and the allies were going so fast that the supplies were hard to follow. Children were asked to pick up the jerry cans that Americans swung along the roads when they were refueling and ended up missing them. We have recovered hundreds. On the railway line, he also passed numerous troop trains. Winter arrived with the cold and the snow, suddenly the Germans attacked in the Ardennes, the famous battle of Bastogne. Patton's troops heading for Metz turned a quarter turn, and for days passed under our windows, a multitude of tanks and trucks loaded with soldiers. As the road deteriorated at high speed, between each convoy, the Americans unloaded tons of pebbles, so that the road gradually rose. At the end of the battle the vehicles passed higher than me. One morning there was a young GI in charge of this work who was shaking cold in front of our house, mom made him come in so he could warm up. On leaving he gave us a bar of chocolate that came from his home, with big nuts, we had never eaten something so good, I will always keep the memory.

In the spring, they had to restore the normal level of the road because several times trucks a bit high hit the railway bridge. This is the first time we saw bulldozers work, we were in awe of these machines. I had caught scarlet fever and it was from the window of my room that I followed this show.

During the following holidays, one evening, the social worker of the railway came to find my mother to tell her that the next day the children had the possibility to go to summer camp in Germany, in the Black Forest. I had to prepare a trousseau. Mad mother thought it was not possible and did not let me go. Other moms had less scruples and the kids left with what they had. When they returned, they were dressed from head to foot, they had among other beautiful tracksuits marked on the shoulder "French Forces in Germany" which were the admiration of all those who did not have. Another serious regret for mom.

May 8, 1945

On the evening of May 8, we were playing ball on the square, when the young men from the village ran into the church and went up the steeple to ring the bells at full speed. That's how we learned that the war was over. For us children, it did not mean much, for us she had finished the liberation. But for grownups it was a holiday like I've never seen since, a collective jubilation, especially with the prisoners who were starting to return. People gathered in the square, began to sing La Marseillaise, someone came with an accordion and they danced like that in the grass until late at night.

t was at this time that we experienced in the press the horrors of the concentration camps. Nobody knew about it. We were horrified by the images of heaps of corpses, cremation ovens, skeletal deportees published among other things in the almanac of L'Est Républicain of 1945.

In our village came families of Poles to work at the lime kilns of Montgrignon, because it was necessary to revolve the metallurgical plants to raise the country. Lime was used to melt iron in Lorraine and all around Verdun there were many quarries and lime kilns. We were not rich, but for them it was really misery: they did not speak our language, the children were badly dressed, they arrived without anything, we considered them a bit like outcasts. Thanks to the school, the children have gradually been able to integrate, but the parents have always remained strangers and yet these people had come to do a job which the French wanted less and less, because to work in these furnaces. was insured silicosis.

The Railroad

The train was the only means of locomotion and my father was a switchman: from a very young age I was immersed in the atmosphere of the railway. Verdun was an important railway center, it was the junction point of four lines: Chalons, Lérouville, Sedan, Conflans. As it was the era of steam traction and there was a large locomotive depot, the railwaymen were about four hundred. Belleville was mainly inhabited by active and retired railway workers and employees of the lime kilns. As soon as I could, I often spent the day with my dad at a switch station. There were five at Verdun: three main stations, substation 1 under the Thierville bridge, substation 2 at the station, substation 3 near the Meuse bridge, and strategic substations 4 and 5 near Thierville. These posts were marvels for me, with their rows of levers of different colors depending on their role, the lights that changed color when announcing trains or lever reversals, the ringtones of different tones. These posts were impeccably clean, each switchman was his point of honor, it was necessary to use skates to walk.

When I was older and my father was at night, I brought him his bowl and I spent the evening with him doing my homework. I remember the particular smell of these posts, a smell of grease because as they were mechanical posts, all the parts were abundantly greased or oiled. This smell, I found many years after when during my career I had the opportunity to intervene in such positions Saxby type.

Many times I had the opportunity to travel with my father on locomotives. When we went to visit our grandmother and there was no train back, we were stuck against the tender, we were hot in front and cold in the back. The railwaymen then formed a big family (they still said they were at La Compagnie) and my father was known to everyone, he was called "The Great Schmitt". By traveling, I knew by heart the names of the stations between Verdun and Lérouville or between Verdun and Châlons.

I was fascinated by the locomotives and I was very excited when we were waiting for the train to Paris at Châlons, and a little frightened when he entered the station. This locomotive was making a huge noise, spewing smoke and steam like a real dragon, and those wheels, much larger than me, and those rods that made them spin, all shining with oil, was a grandiose spectacle.I knew the main points of the line: Epernay and its Castellane tower, the statue of Urbain who greeted us in passing, Château-Thierry and the curve of Pisse-Loup where by leaning out the window we could see both parts of the train. I knew when we would enter a tunnel. When I arrived in Paris, my face was black and very often a dart in one eye. You did not have to be dressed in white at that time to take the train.

Go and find out why, when I had to choose a definitive job, I entered the railways. A story that comes back to me about trains, it was in 1944, mom came back I guess Sampigny, the train was crowded with German soldiers. They talked to each other about the war in Russia, they said that it was horrible, that the soldiers were dying of cold: when they put pants, they sometimes had the genitals or the anus frozen. At that moment, one of the soldiers realized that Mom was listening to them, he said to his comrades "This little lady seems to understand us" and they started talking about something else. This story, mom told us when we came home and many people have had a hard time believing it.

The years after the War

My little sister Bernadette was born in January 1946, the women then gave birth at home. When the day arrived, the midwife locked herself in the room with Mom. We were waiting in the room next door. Dad was very nervous and did not want to make any noise. Suddenly we heard a baby screaming and the midwife opened the door telling us it was a little girl. Dad rushed into the room, I went a little later and I was able to kiss the baby. This is where Mom explained the mystery of birth, of course without going into too much detail.

There was also the baptism of my little cousin Danielle at Colombes. I stayed on vacation for several weeks. My uncle Andre had built his own house at Petit Colombes. There was then very little construction, in front of them there was a wasteland that went up to the Seine and where, with young children from the area, I spent long days playing. In their garage, there was also a car that no longer worked, inside which we made beautiful imaginary journeys, a car that would certainly be very expensive from a collector. I think that's where I had my best vacation. Uncle André knew how to do everything with his hands and I liked to tinker with him. Theuncle and aunt resold their house to buy a shop in Damville in the Eure, once I had the opportunity to go to Colombes, I tried to find their flag, but it disappeared and the vacant lot, replaced by frightful constructions.

In 1946 I went to summer camp at the castle of Hattonchatel near Saint-Mihiel in the Meuse. It is a castle that was rebuilt after the war of 14 by a rich American woman and donated to the bishopric of Verdun. We were surrounded by abbots, one of whom had been interned at the Buchenwald camp as a resistance fighter, he was reluctant to tell us what had happened there.

We made camp fires, night games, we participated in hunting darut, a young man held a burlap bag open against a bush, others with a stick tapped on this bush shouting: "darut, in the bag "and that in the dark because it was not necessary to scare the beast. It was not a good year because we did not capture it.

In 1947 I went for a month in an SNCF holiday camp at the Markstein in the Hautes-Vosges. There it was a little different, the monitors had just been released from the service and there was a somewhat military discipline. We had to make our beds squared, in the morning and in the evening there was the hello to the colors. We hiked the balloon from Guebwiller or Grand Ballon to the Schlucht or the valleys, Lauch Lake or Felering. The lumberjacks were still coming down the wood at the schlitte. We had a cure of blueberries, we smeared the body and we put ferns around the waist, we disguised ourselves as Indians. We stayed for several days with the body dyed blue.

In the month of October I entered college, sixth, I feel that it is the turning point of my life and the end of my childhood. I stop writing my memories.

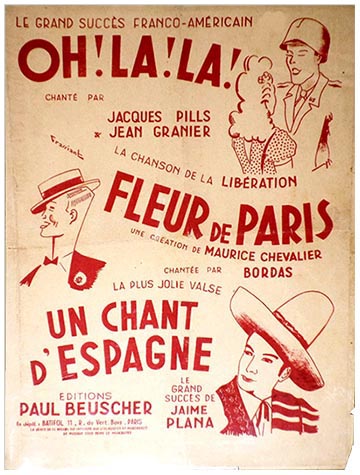

Music and Songs

I would like to finish by talking about the hymns or songs that marked that era. Already I remember that in the early days of my schooling, we began the class by singing "Maréchal nous voilà, devant toi le sauveur de la France..." standing before the portrait of Marshal Petain represented with Francis. I do not know if it was a private initiative or a directive, since it did not last long! We had no right to sing La Marseillaise. During the war, the children did not know her, but what an emotion when we heard the people singing her fervently for liberation and at the patriotic festivities that followed, whether on the fourteenth of July or the eleventh of November. So many people died for singing it or died singing it.

At the patronage we sang "Mais qui n'a peur de rien mais de rien c'est Tintin,

mais qui le suit partout et partout c'est Milou. Quand on voit Tintin, Milou n'est pas loin car Milou

le brave Milou suit Tintin partout."

The post-war songs were the joy of the joy of living of the newfound freedom.

retrouvée.

"C'est une fleur de Paris et de Paris qui sourit",

"Mademoiselle from Armentières",

"Ca sent si bon la France",

"Il fait bon chez vous Maître Pierre"", All those songs and many more that we sang while we were in a group and left so many good memories. We must not forget the American rhythms, the swing, the jazz on which the youth rushed and which made us glimpse better days.

A song that was also a huge success and was released in 1947 at the time of my little cousin Dany's baptism: "Ah le petit vin blanc, qu'on boit sous les tonnelles…" and the first Bourvil songs that were a little "cucul" but that made us laugh.

A different Time

It may be that I made some mistakes in the dates, that I confused two years, I apologize but I think that it is not very serious, because I can certify that all the facts related have well existed and that I lived them.

Those who read my prose may think I had a troubled childhood, yet I remember a happy time. I think children live from day to day and they do not really realize how serious the events are. Although pulling the devil by the tail, our parents have always arranged for us not to miss the necessary. Dad practically never had any leisure between her work, her gardens, the cutting of the wood ... Mom with the little she had managed to make us good dishes, she spent hours and sometimes nights on her machine sewing to make clothes. They have never been on vacation, except for a few days in the family in Colombes then in Damville. Once, however, in 1953, while I was in the navy at the Bormettes radio school near Hyères, they spent a week at the edge of the Mediterranean. It was the first time they had seen the sea, as I did, because I had to get involved in the navy to see it. I had the exceptional permission to go out at noon and in the evening to eat with them. It was at the height of the mimosas, they filled a suitcase to bring back to Belleville. This stay remained one of their best memories.

This period has taught us to recognize the value of things, now I hate waste. I was outraged when lately we did a transatlantic cruise, we could practically eat from eight in the morning until midnight and up, people were filling up big plates that they left and that went in the trash. When I think we were served by people who came from third world countries, back home they had to say that we were real bastards.

One last example, when I was fifteen, my parents decided to pay me a bike to go to college, because I was typing about eight kilometers every day, two in the morning, two at noon to eat, two to thirteen thirty in the evening. Very often I had to go back to Verdun to go on errands like going to the pharmacy. This purchase was a big sacrifice, more than two months salary, and yet it was a very simple bike with a three-speed derailleur, without a double plateau. He was of the brand "Arliguié, the brand that goes up". My father went to buy it in Verdun and as it was raining, he came back carrying it on his back so that it would not be dirty. I made kilometers with this bike,with comrades we visited all the battlefields of the region and that is not what was missing, it happened that we made a hundred kilometers in the day.

Of course we did not have a refrigerator, much less freezer, no vacuum cleaner, no washing machine, no TV, we did not even know the ballpoint pen, it all came much later, which did not stop us from having a happy life and perhaps richer and happier than the children of today.

We were free, we could swim in any watercourse without a lifeguard or a gendarme to call us to order. Our parents let us go, there was no feeling of insecurity. We did a little what we wanted, nature belonged to us. We played in all the forts around Verdun, going down inside to collect some powder that was being burned, especially in the Fort de Moulainville. Rockets were made from tin cans, which were filled with powder and crushed. Now all these forts are forbidden.

One thing we did often and would not be possible today: Verdun is surrounded by rather steep hills, the Etain coast, the Rozellier, we waited for a truck to overtake us and as it was not going fast, we catch up and we hung behind. Some did not like it and made sure to force us to let go by hugging us on the shoulder, so we were hanging on the other side.

It may be an idea, however, because everything must look better in the memories of childhood.

Avenay-Val-d'Or, April 2004